The Austrian boom phase provides the “illusion” of growth and there are structural reasons why it must unwind. As distinct from other schools of thoughts that rely on amorphous channels of “confidence”, the Austrian story contains the seeds of recession within the boom. To sum up the theory in a nutshell:

“True, governments can reduce the rate of interest in the short run. They can issue additional paper money. They can open the way to credit expansion by the banks. They can thus create an artificial boom and the appearance of prosperity. But such a boom is bound to collapse soon or late and to bring about a depression” Mises (1944) p.251

ABC rests on the claim that artificial credit expansion leads to unsustainable investment projects. Easy money and subsequent low interest rates encourage firms to borrow money and invest in interest-sensitive projects, and for consumers to consume rather than save. As Garrison (2001) points out this causes the economy to pull in two directions at once: cheap credit is fuelling malinvestment, whilst strong consumer demand leads to over consumption. The typical assumption is that this “tug of war” over the stock of real resources tends to be “won” by the business sector, because they are closer to the source of credit creation.

The problem stems from the separation of credit and prior production (i.e. savings). Credit allows us to draw upon expected future income streams; therefore if we use credit to fund investment we are anticipating that the value of those future goods will exceed the interest costs of the loans. But note that if we draw upon future income for present consumption, we’re merely engaged in capital consumption. The problem occurs when we systematically overestimate future incomes, and borrow against future income/profits that doesn’t materialise. Since the interest rate is the signal that provides coordination over time, Austrians tend to focus on the manipulation of it as the cause of these clusters of errors.

When outlining the stylised facts of an “Austrian” business cycle it is again necessary to be wary of the hindsight bias – having recently “experienced” a boom-bust cycle it would be tempting to claim too much. Indeed the intention of this post is not to explain every detail of the cycle, but instead to draw upon the “stylised facts” and compare them with real events. This section of the article is not theoretical, and therefore it is possible that competing explanations also provide a “fit” for the data.

Since most work on the Austrian business cycle theory is academic, there are surprisingly few accounts that commit to outlining how markets will look at various stages. However if this post sought to distil and/or blend existing work it would increase the potential for taking a selective view. Therefore the paucity of literature will be embraced, thus making it easy for readers to verify for themselves that this is a faithful and complete recounting of the sources used! I will rely on two main sources, each providing slightly different points of emphasis. I may be accused of being a little biased, and I can take that. This is, after all, my creed.

“I say “creed” because, for brevity, it is purposely expressed dogmatically and without proof. But it is not a creed in the sense that my faith in it does not rest on evidence and that I am not ready to modify it on presentation of new evidence. On the contrary, it is quite tentative. It may serve as a challenge to others and as raw material to help them work out a better product” (Fisher, 1933 p337).

Oppers (2002) will be used to provide the underlying contours and general description of what Austrian’s might expect to be occurring. Skousen (1988) will be utilised to make specific claims about key indicators and asset classes.

Phase A: The inflationary boom

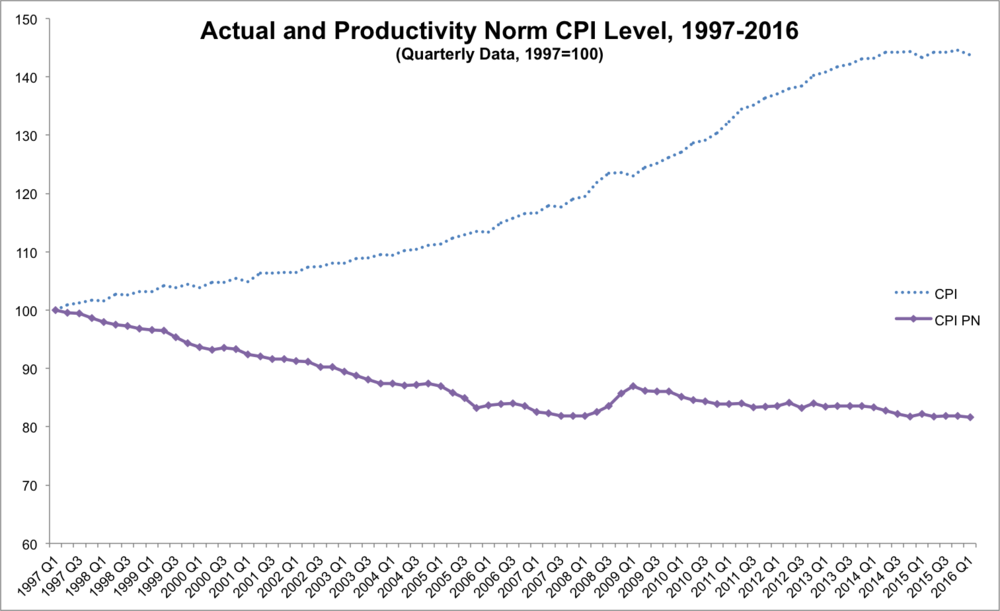

During the boom it will not be clear that there is a problem, since superficially the main economic indicators will suggest that the economy is running smoothly – there will be robust increases in economic output, low inflation, and strong confidence. Oppers (2002) points to three issues that would concern Austrians, however:

- “Strong investment demand in particular sectors (this could lead to stronger than warranted building up of production capacity)”

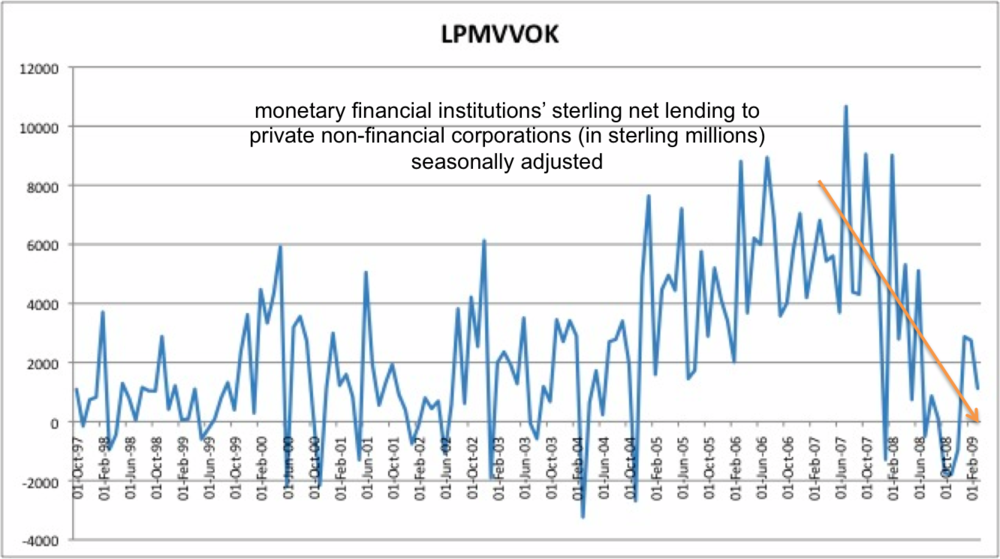

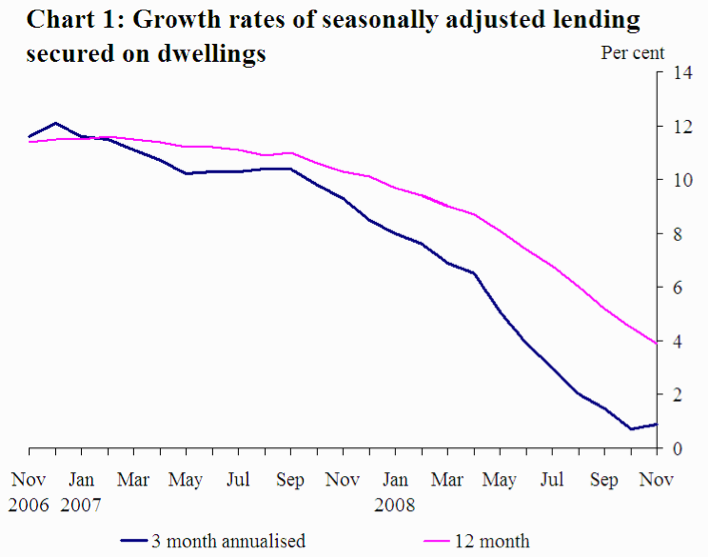

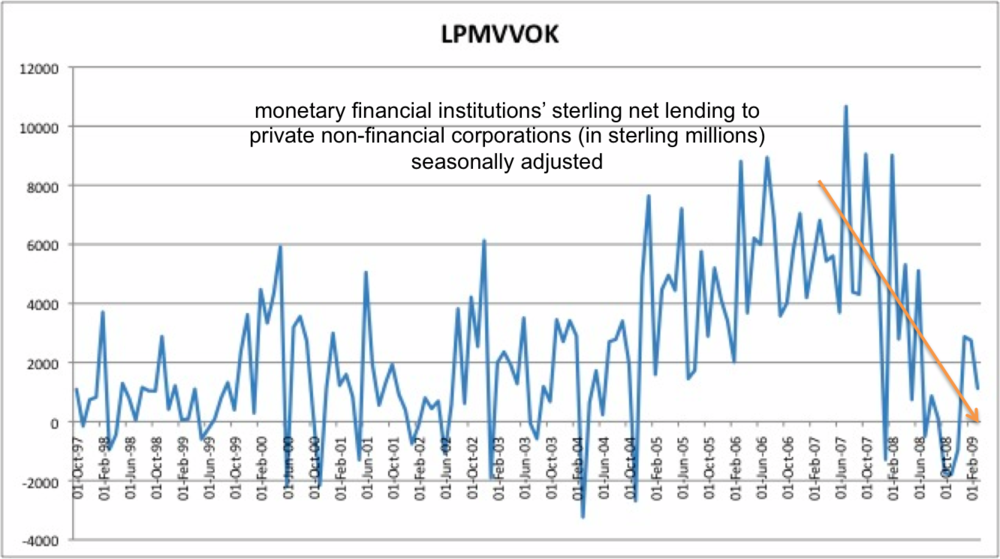

- “An expansion that is driven by strong growth in credit, especially to enterprises”

- “a diversion of resources away from the production of consumption goods towards capital goods, with an associated rise in consumer goods prices relative to those of capital goods”[5]

Following Skousen (1988) we can generate four empirical generalisations:

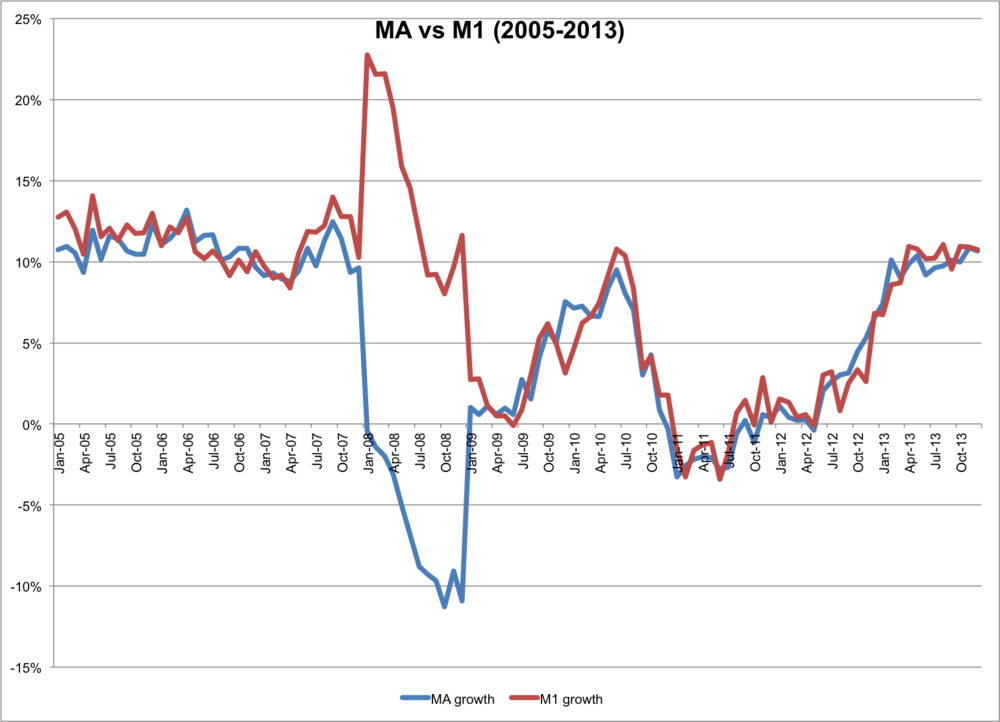

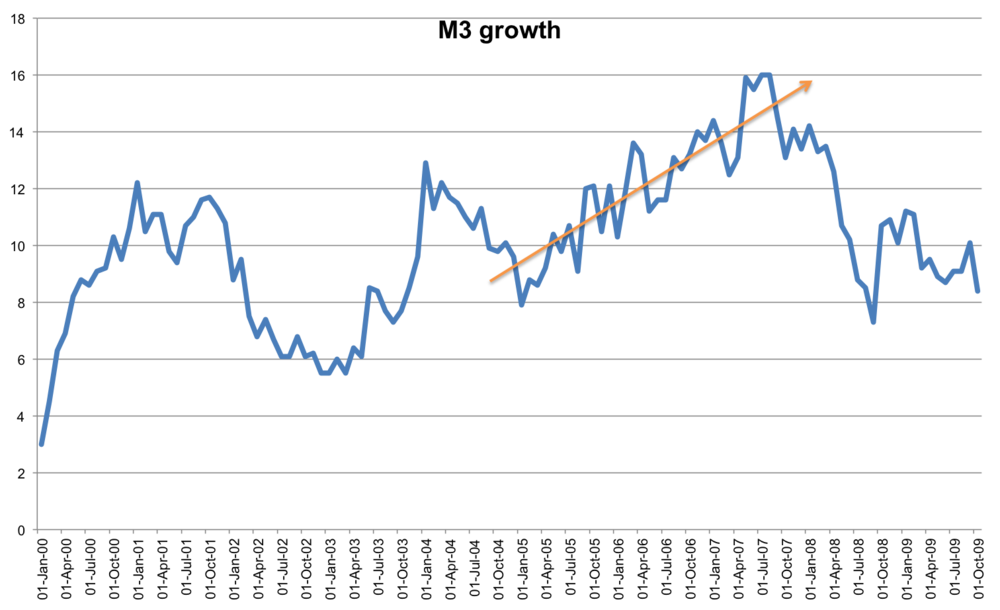

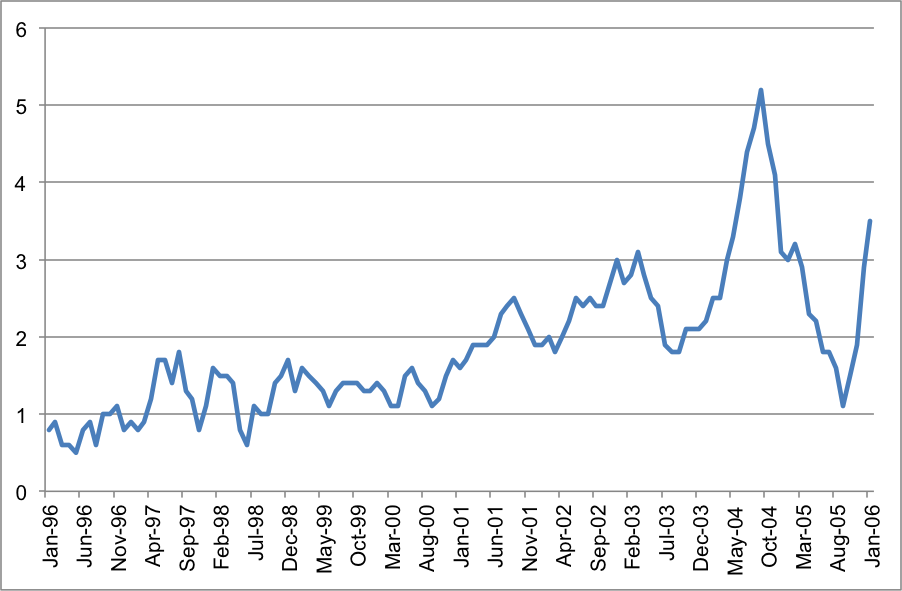

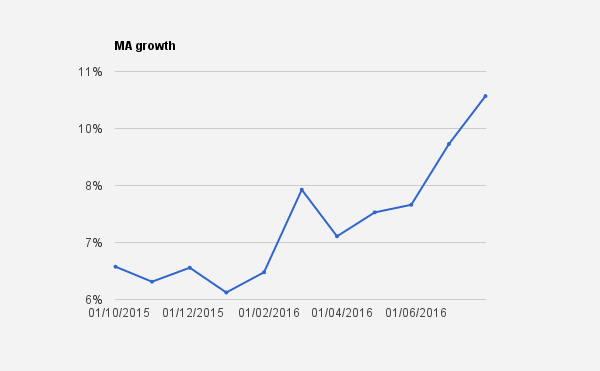

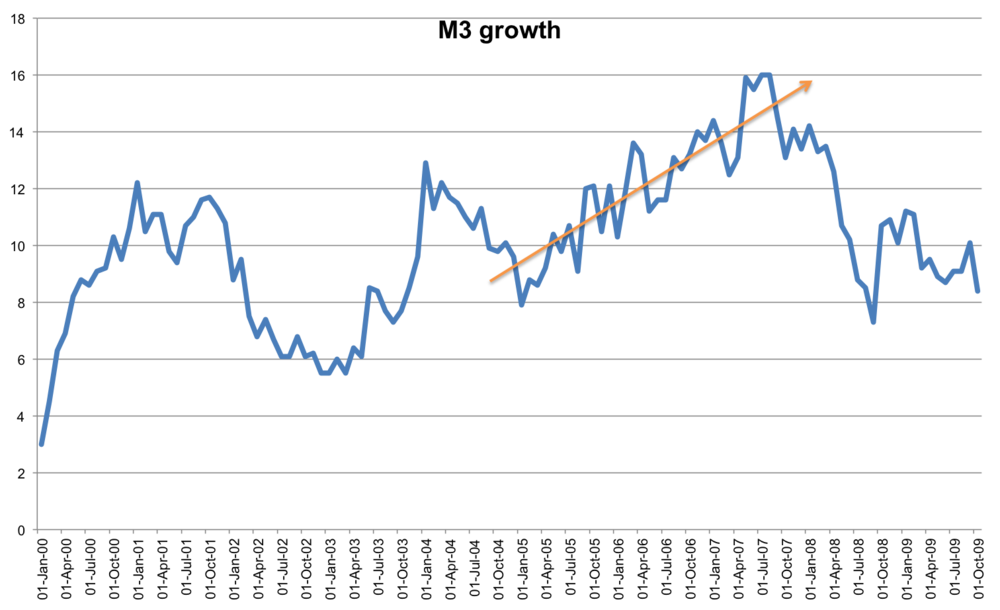

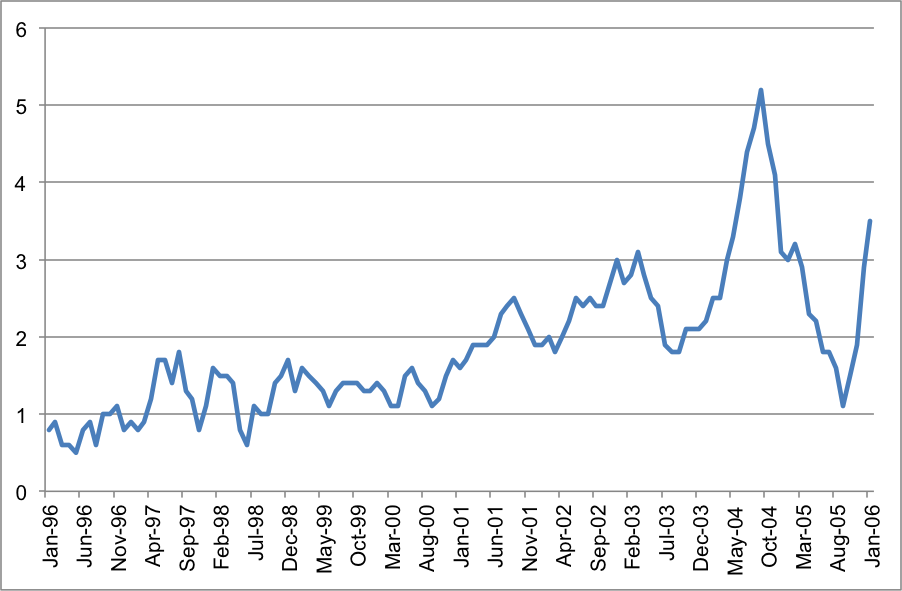

A1: an increase in the money supply

It is this that drives the cycle, and is what pushes the interest rate below its “natural rate”. The fact that capital-intensive industries are stimulated leads to two related observations:

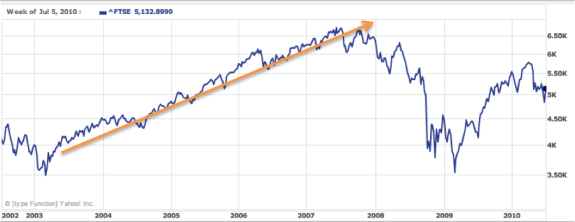

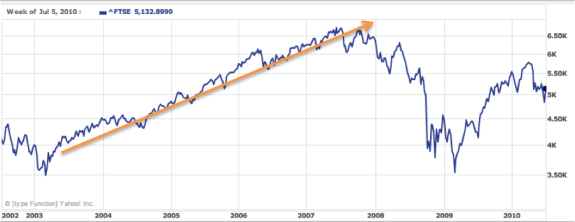

A2: a rise in corporate profits and

A3: a stock market boom

Finally,

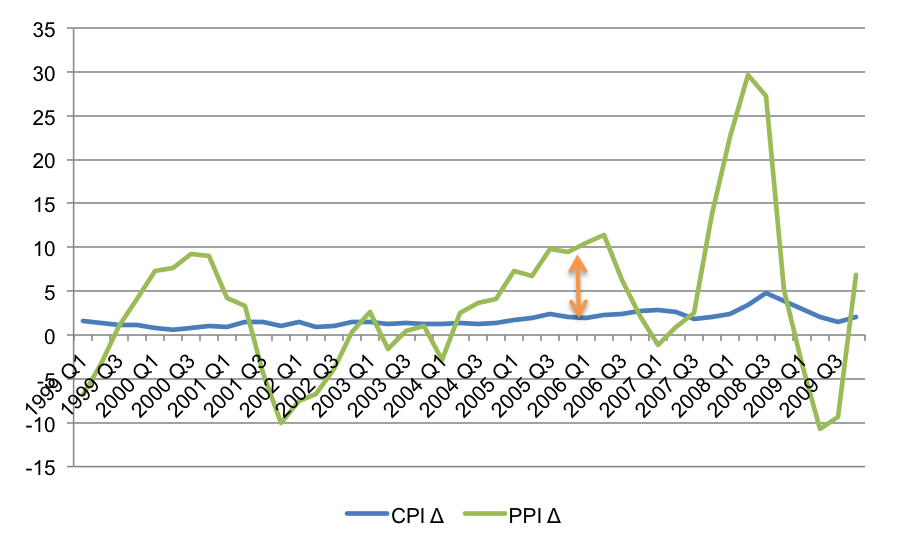

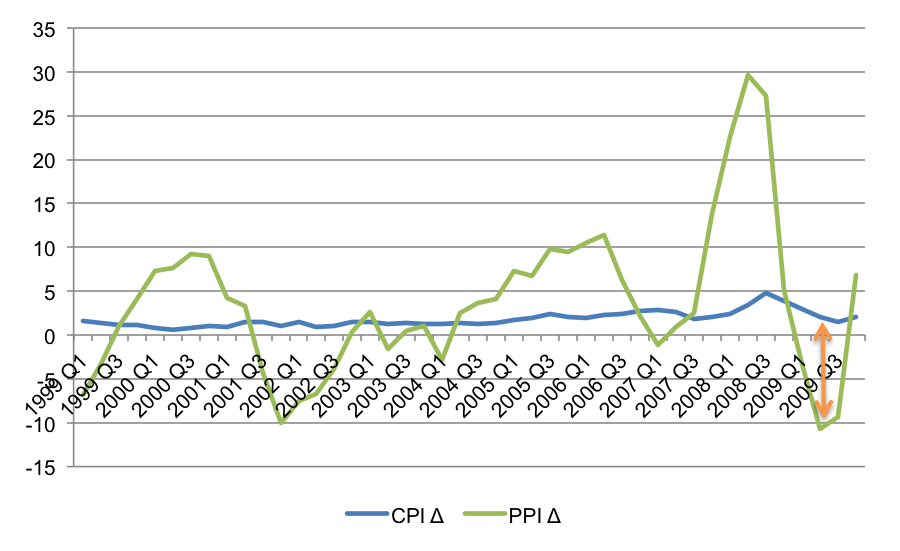

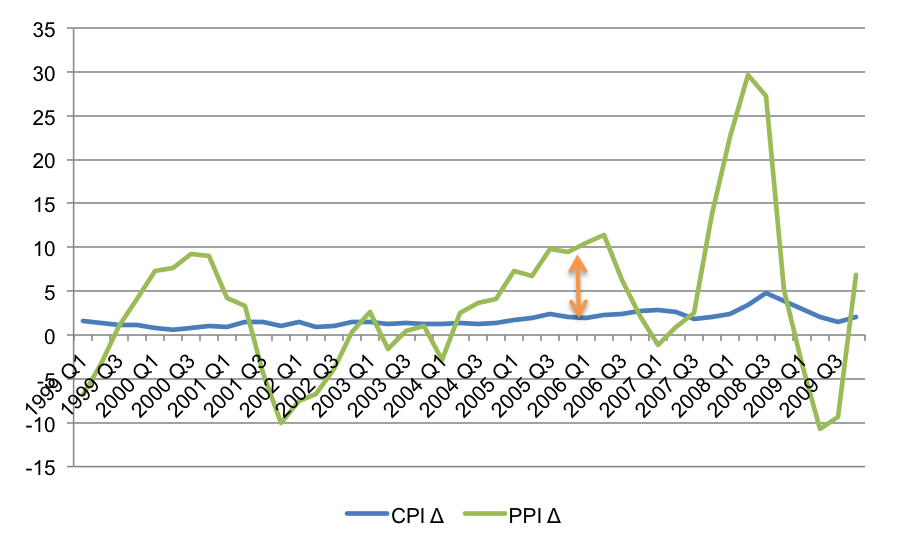

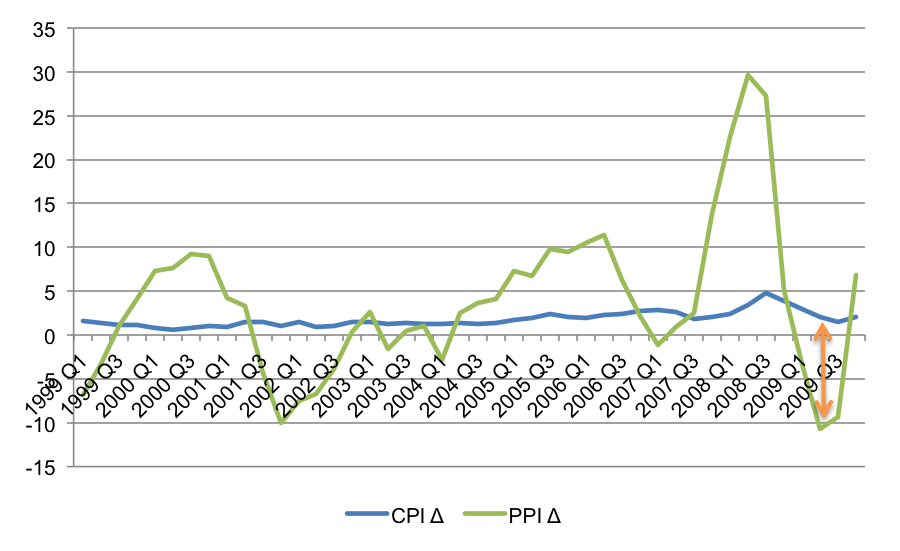

A4: the producer price index rises faster than the consumer price index

Phase B: The credit crisis

The credit crisis itself might be considered a “moment”, however we can attribute several observable events to this phase of the cycle. This is the point at which “earlier malinvestment becomes apparent” (Oppers 2002), or where the “illusion” of growth is revealed. Again, Oppers (2002) provides commentary:

- “a capital stock that is badly matched to the structure of demand”

- “excess capacity in certain sectors, and a lack of capacity in others”

- “the slump would likely also be felt strongly… in the banking sector, which would see its loan portfolio deteriorate, as highly leveraged investment projects undertaken during the boom prove to be unprofitable”

According to Skousen (1988) this phase of the boom will manifest itself in the following ways:

B1: The consumer price index begins to catch up with the producer price index

This leads investors to flee into inflation hedges, leading to:

B2: A rising gold price

B3: A rise in the price of commodities

The fourth impact will be

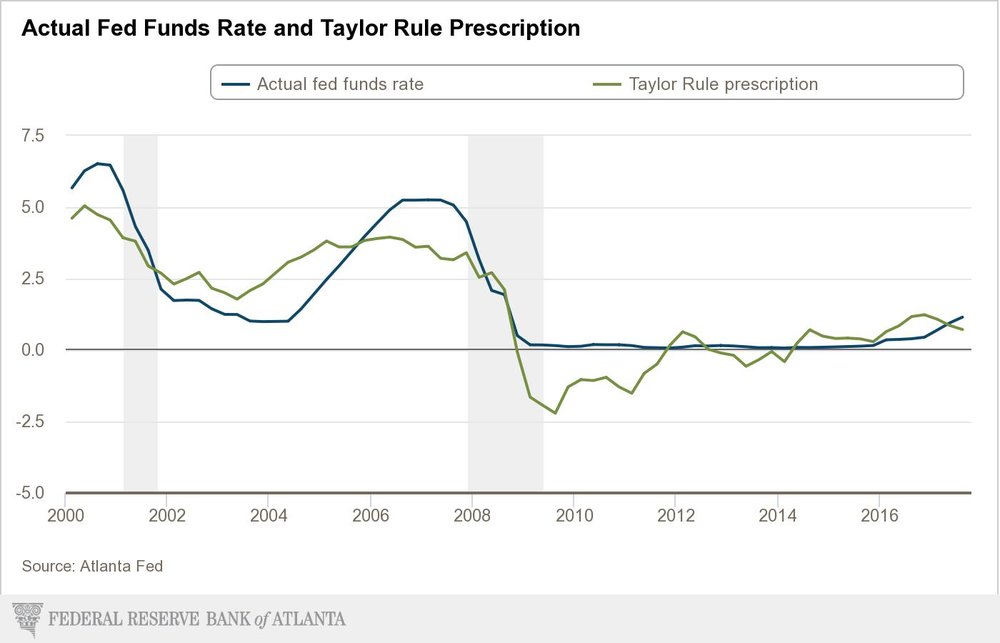

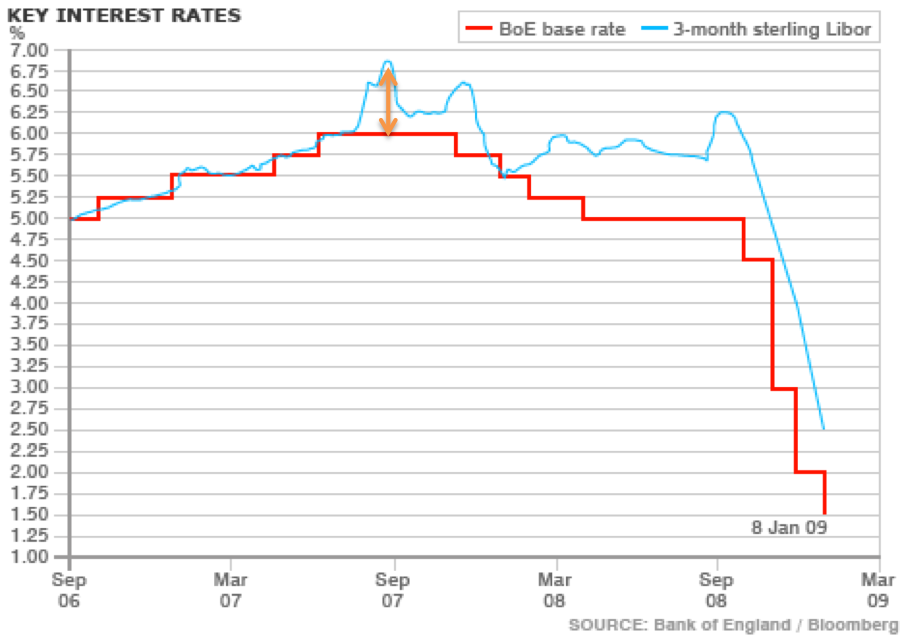

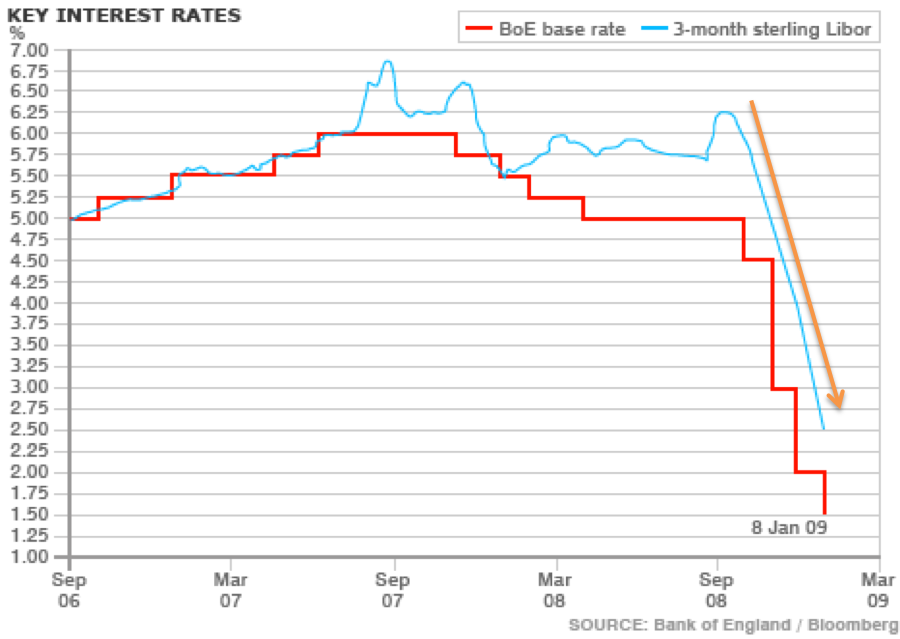

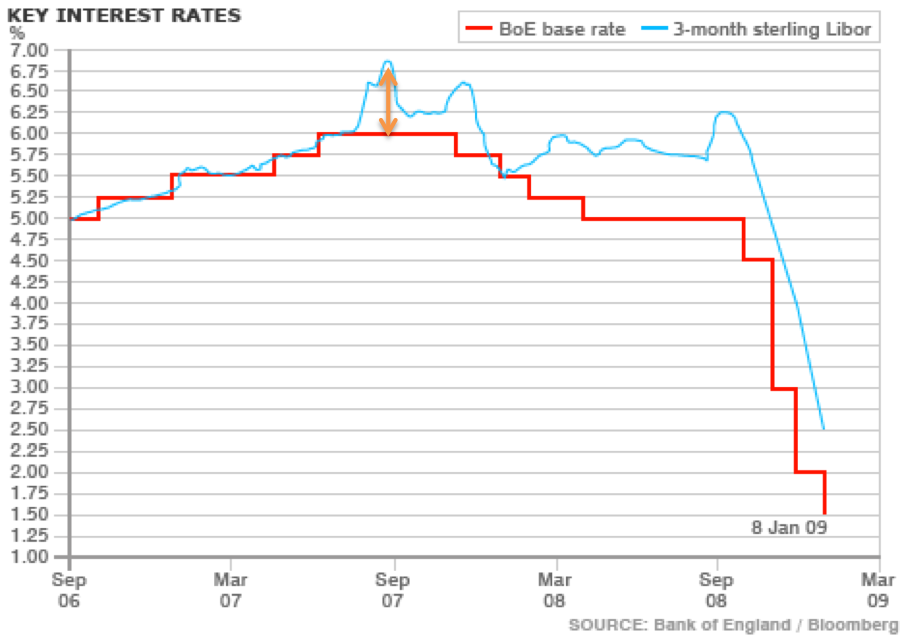

B4: Rising pressure on interest rates

And this stems from two forces. On the one hand the manifestation of consumer price inflation will likely lead to policy responses from the central banks. Also, higher interest rates will reflect the fact that banks seek to call in loans to preserve their balance sheets, reflecting

B5: Banks and corporations scramble for funding

Phase C: The recession

During the recessionary phase the policy debate comes to the fore, as Oppers (2002) writes:

- “they [Austrians] see demand-stimulating policies after the cyclical peak as merely postponing (and thus potentially aggravating) the correction of past excesses”

- “an economy in recession does not respond well to expansionary monetary and fiscal policies”

However the recession itself is a fairly unambiguous phenomena, and we would expect to witness typical economic indicators:

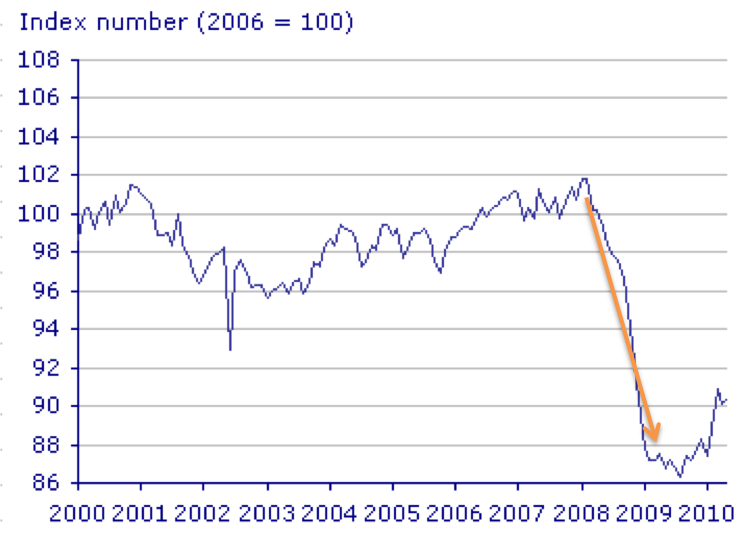

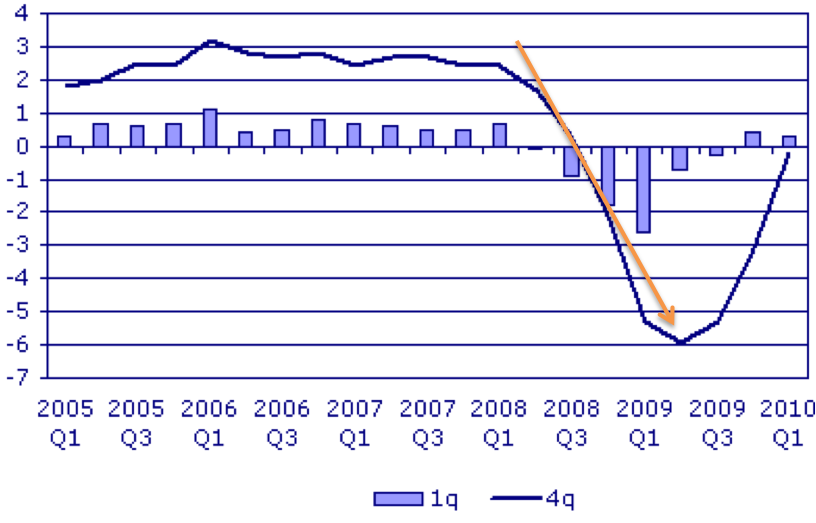

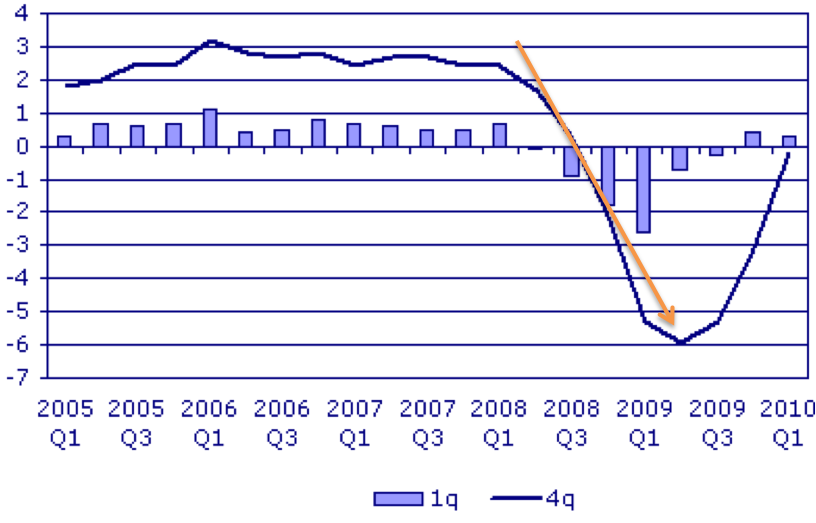

C1: Production of capital goods falls more sharply than consumer goods. (There is evidence that activities furthest from consumer spending were more severely affected by the recession. Whereas the service sector saw a year on year decline of 3.1%, industry fell by 12.5% whilst construction fell by 13.2% (Giles, C., and Pimlott, D., “UK economy shrinks most in 50 years” Financial Times, June 30th 2009)). As Hayek says,

“It is the decline in investment (or in the production of producer goods) and not the impossibility of selling consumer goods at remunerative prices, which characterises the beginning of the slump” (Hayek 1932)

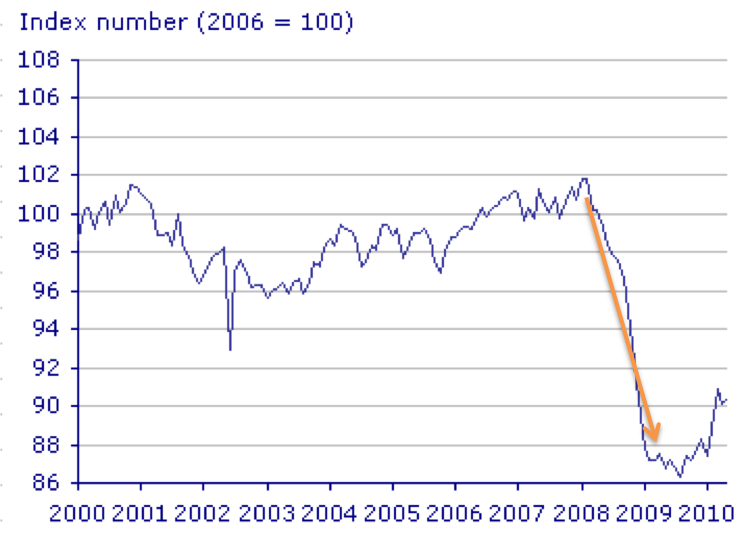

C2: A fall in GDP

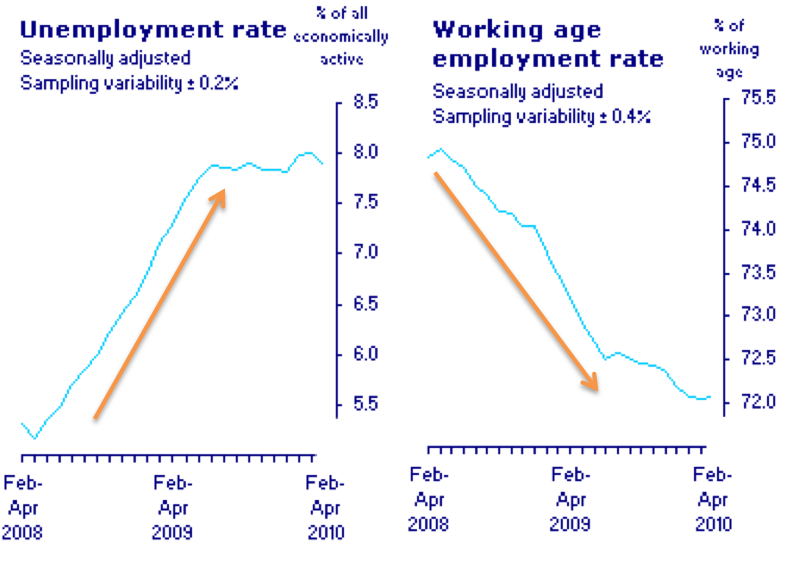

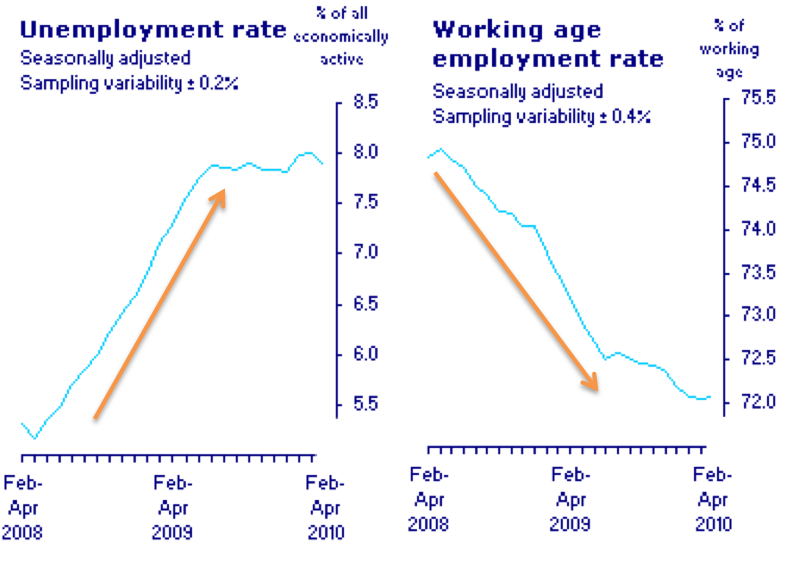

C3: A rise in unemployment

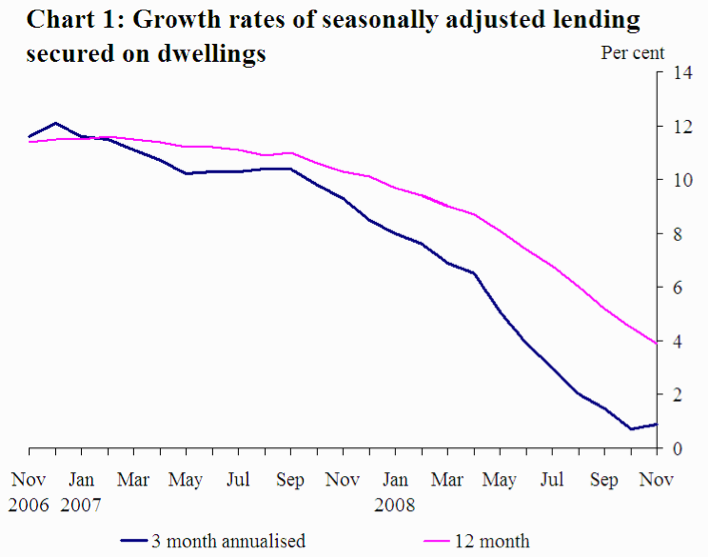

Since the demand for credit declines and central banks engage in expansionary monetary policy we would expect:

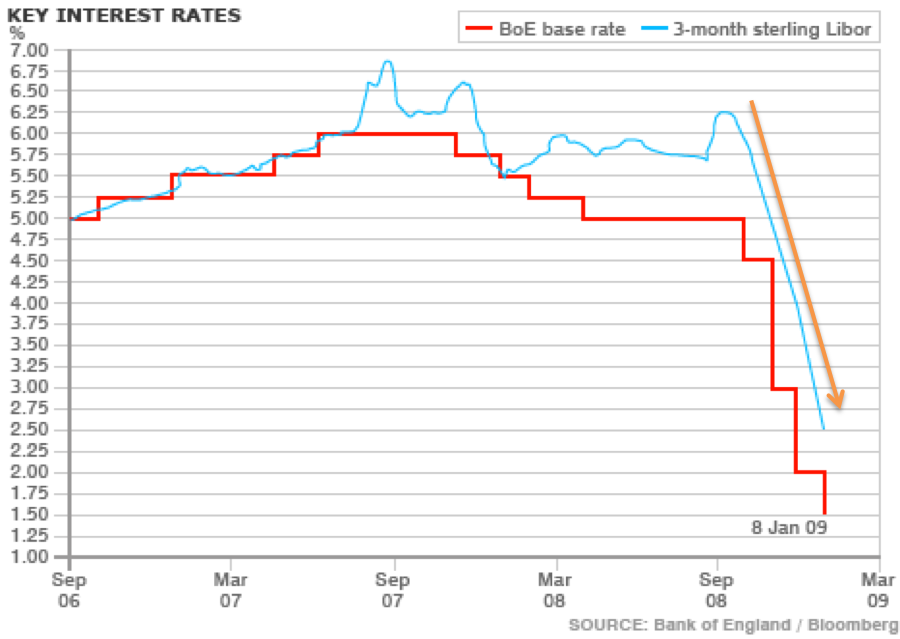

C4: Falling pressure on interest rates

And finally:

C5: The producer price index falls by more than the consumer price index

We can also draw upon Fisher’s (1933) debt-deflation theory sand outline 9 stages of liquidation. These are, (i) distress selling; (ii) reduction in velocity of deposit currency; (iii) fall in the price level; (iv) fall in the net worth of businesses; (v) fall in profits; (vi) reductions in output and employment; (vii) reduction in confidence; (viii) hoarding and further reduction in velocity; (ix) fall in nominal interest rates, rises in real interest rates.

Phase D: The recovery

I think that “the recovery” is an analytically distinct phase to “the recession” even if in practice they tend to coincide. However in reality the likelihood that government responds proactively to “the recession” means that genuine recovery is often jettisoned in favour of a return to an inflationary boom. Despite this we may retain a fourth phase – after the adjustment costs have been borne, and the fruition becomes evident.

I find the evidence compelling.