The term "roundaboutness" is often used in Austrian business cycle theory, and I'm not sure if it's a simple term being consistently applied, or something more complex. At the recent APEE meetings Nicholas Cachanosky presented a paper arguing that it isn't a mysterious concept (co authored with Peter Lewin), but I'm not sure I'm convinced. My basic understanding, stemming from Bohm-Bawerk is the following:

Roundaboutness = capital intensity.

Cachanosky & Lewin define roundaboutness as the "average period of production", and use net present value formulae and the concept of EVA to measure it. This is a great way to operationalise the concept, but is it "roundaboutness" that is straight forward, or their method?

One of the reasons I find Tyler Cowen's "Risk and Business Cycles" unsatisfying is because he doesn't really allow for different types of risk. In his treatment "risk" does all the work, and there's no need to talk about roundaboutness. I can't help feel that this fails to do justice to the Austrian story. Hence I am always wary of the following characterisation:

Roundaboutness = Time = Risk.

We can think of the interest rate as a measure of our time preference (or the ratio of the value of present goods to future goods), or a market generates risk assesment. Must they be the same thing? All else equal the longer the production process the greater the risk, but we can conceive of production plans that are risky but immediate (e.g. fashion) and those that are not so risky but distant (e.g. oil wells). In other words risk and roundaboutness are conceptually distinct.

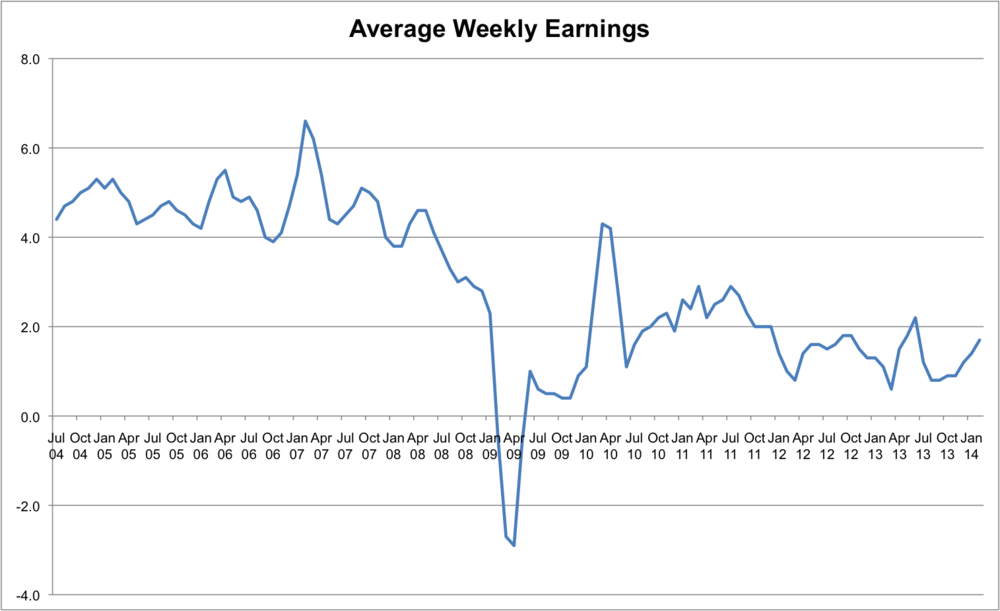

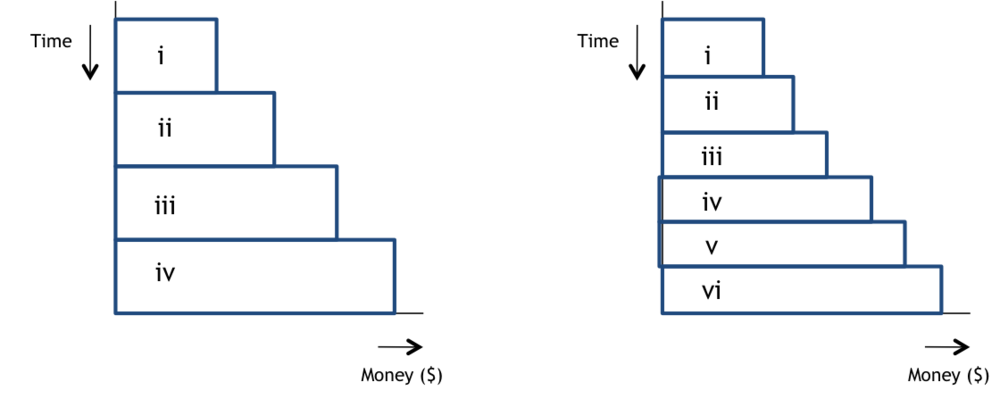

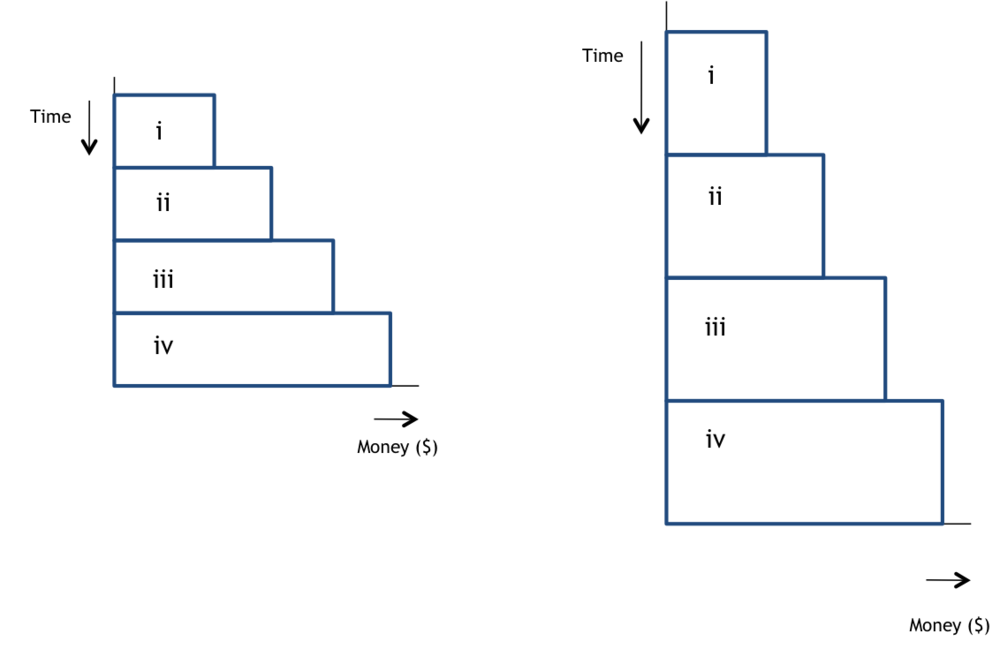

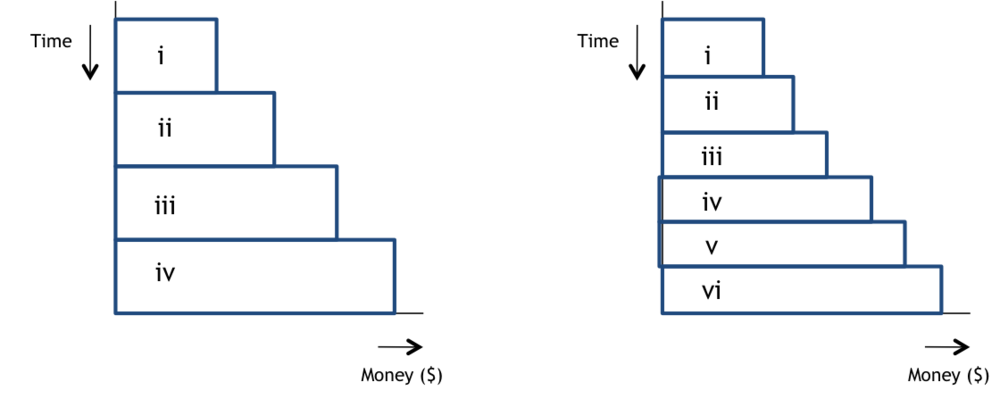

Consider a standard Hayekian triangle:

Now, whilst playing around with these diagrams can go too far, I think they're a good way to illustrate my point. Consider these two alternative ways of treating roundaboutness. Firstly, aa an increase in the production period:

Alternatively, roundaboutness could mean that there's more stages of production:

In the example above the final value of the consumer goods being generated is the same, but the value at all stages of production has increased. We could also show this where there's a change in the composition of the value from late stage to early stage:

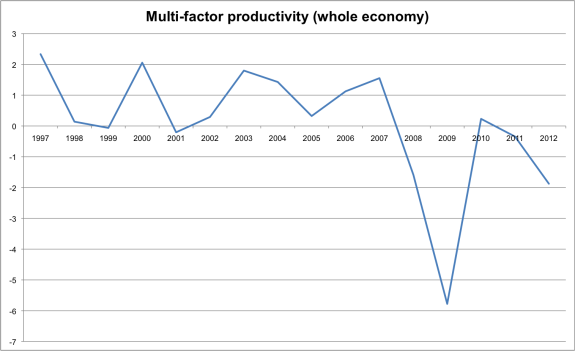

And so on. It would be interesting to assign some possible applications to show that this is empirically relevant.

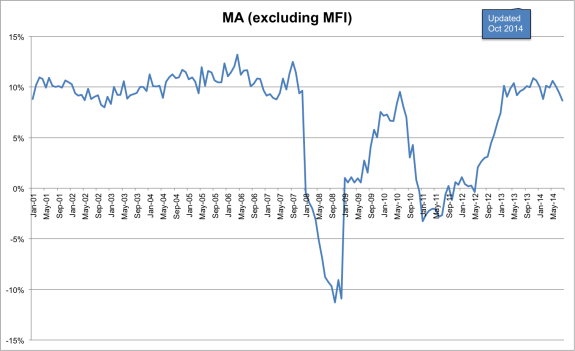

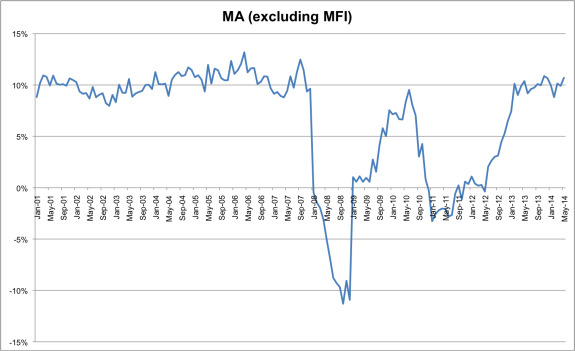

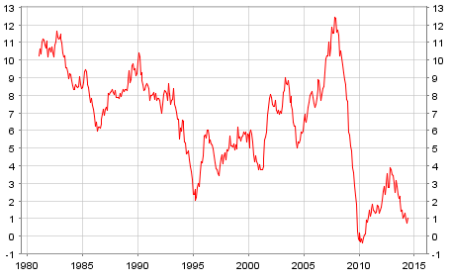

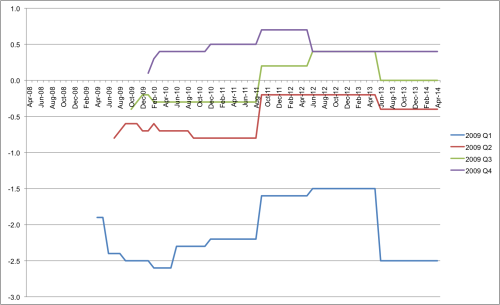

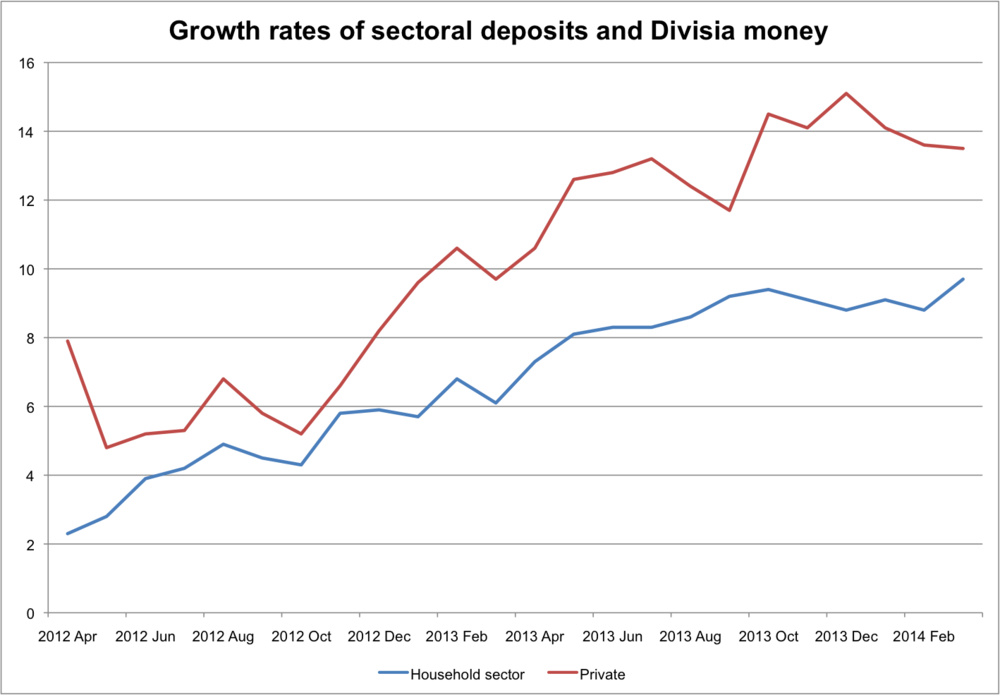

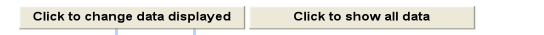

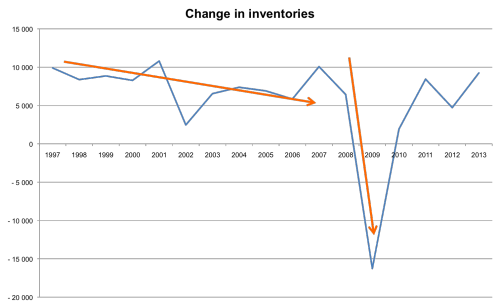

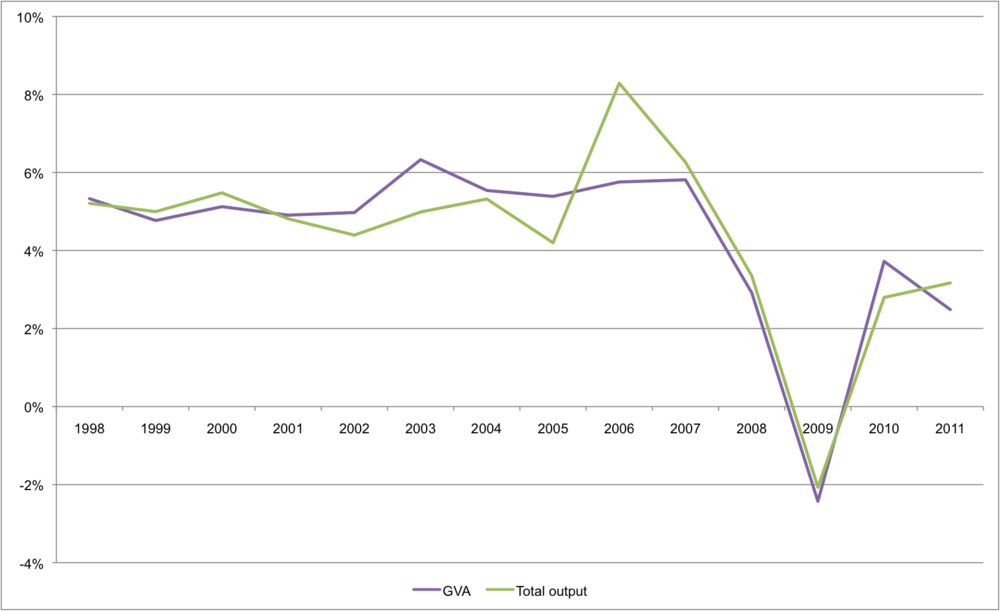

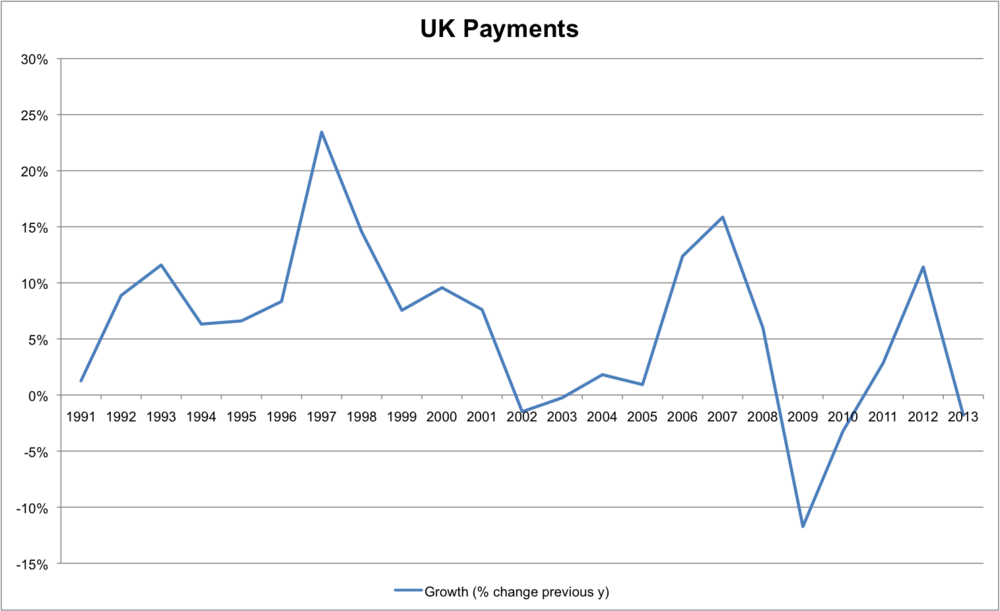

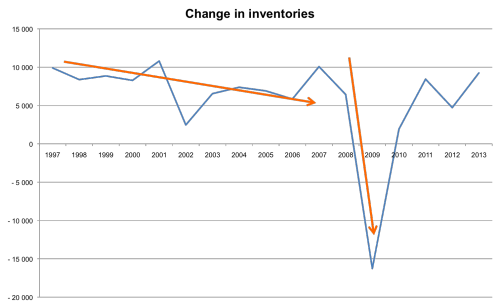

When sketching out these triangles I have in mind Lachmann's notion of reserve assets, which has recently been utilised by Robert Miller with his treatment of "buffer stocks" (here and here). It's hard to measure buffer stocks, and it's tempting to use inventories as a starting point. Here's what's happened to inventories in the UK over the last few years:

What we (sort of) see here is a steady decline in inventories from 1997 - 2007, which point to two things. Firstly, they get run down because excessive optimism means that entrepreneurs don't feel that they need them. And secondly, the utilisation of inventories as a means to generate unsustainable production (i.e. go beyond the PPF). Then during the crisis there's a dramatic reduction in inventories, and the "recovery" involves rebuilding. We need to be careful though, since inventories are just one source of buffer stock (and indeed one that is particularly close to consumer goods or final stage production). Some examples of buffer stocks include:

- Inventories

- Cash balances and other liquid assets

- Commodities (not only as aproduction input but also as a speculative hedge)

- Labour

- Any goods that are relatively less heterogeneuous that others and thus adept at fitting into an array of alternative production plans

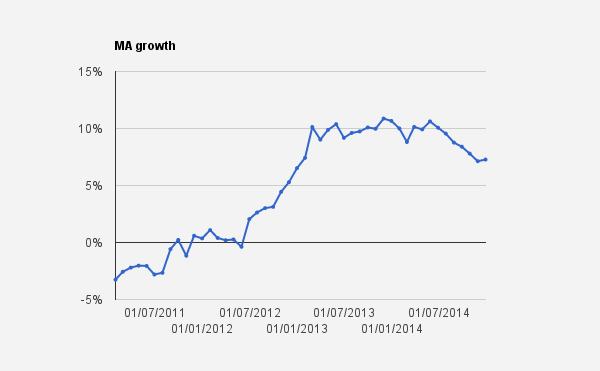

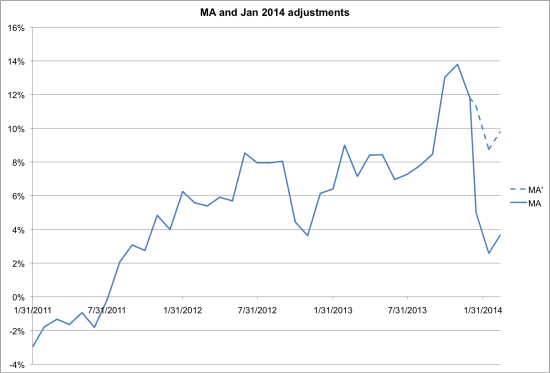

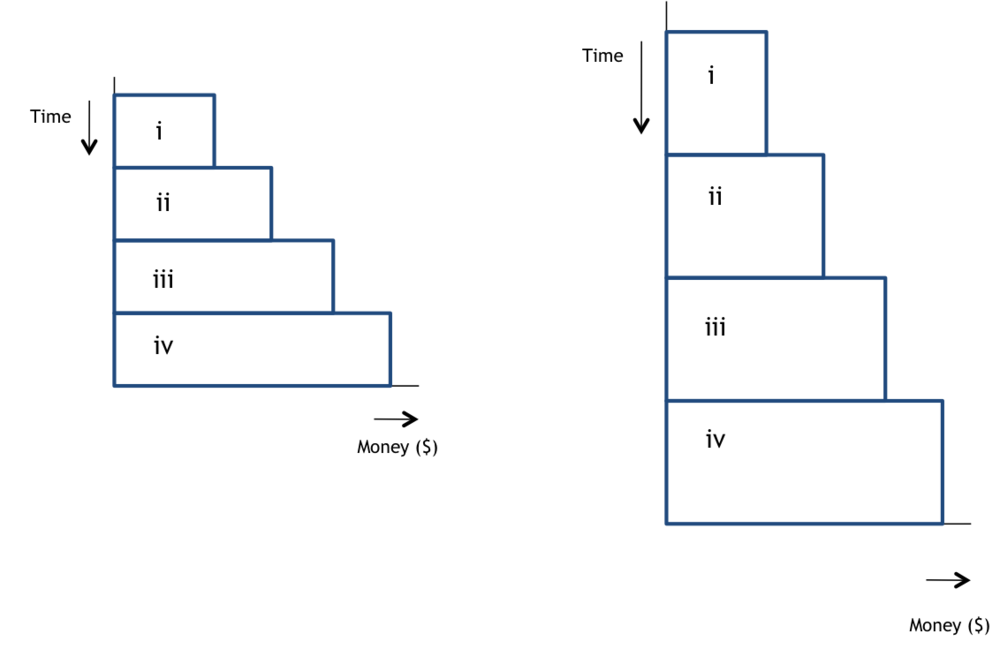

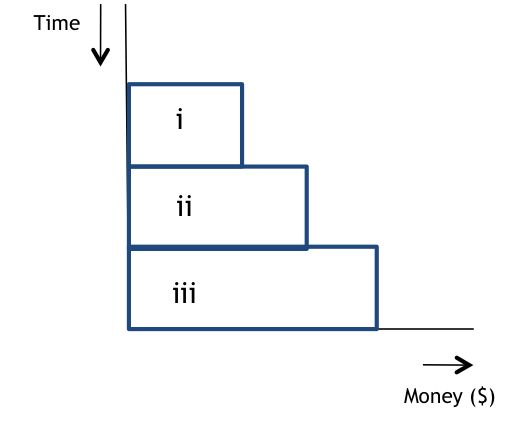

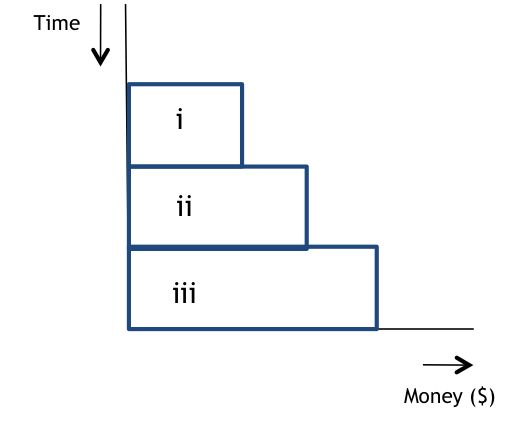

Finally, consider a Hayekian triangle and what's supposed to happen when interest rates fall. For simplicity, let's go use a 3-stage version.

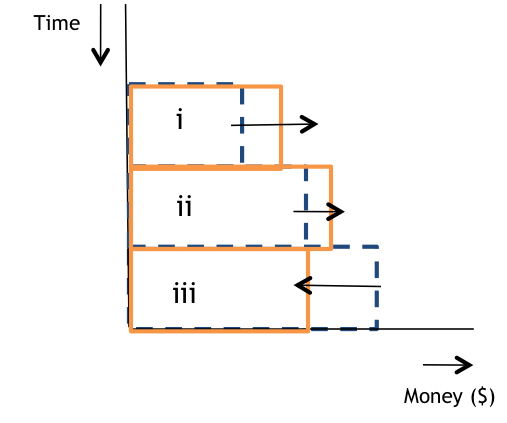

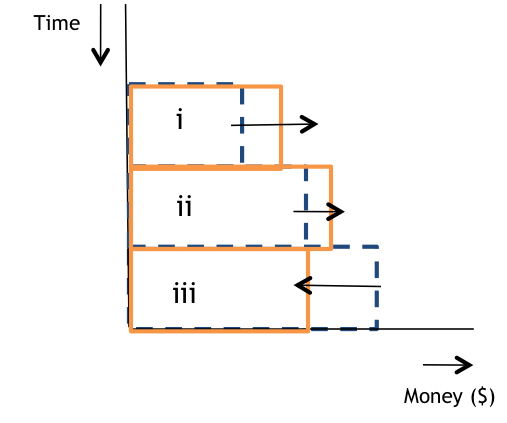

If lower interest rates induce entrepreneurs to move towards more roundabout methods we would expect resources to move from stage iii back to stage i. But stage iii is substantially larger than the early stages. Let's say we shift around 30% of the value in stage iii to stage ii, and likewise from stage ii to stage i. Here's (roughly) what we might see (original is dashed):

Is it not conceivable that the reduction in stage ii (as a result of activities being shifted to stage i) is offset by the shifted production from stage iii? In other words lower interest rates will cause unambiguous reductions in late stage production, increases in early stage production, but may also swell mid stage production? The stylised facts would be an increase in stage ii.