I know that many economists dismiss Steve Keen as a crank (and by “crank” I mean an unserious thinker who refuses to subject their views to an honest critique) but I respect and admire the way he draws upon heterodox ideas and forms compelling narratives. So I was grateful to him for a recent dialogue that we’ve had on X.

(Since X requires you to be logged in to view posts, and because some of the threads can be hard to keep track of, I will post screenshots below. If Steve chooses to reply to this article I would hope that he acknowledges that these are all genuine posts and that I have represented his statements fairly).

It began by him joining a thread that he was tagged in, and being rude about George Selgin.

George is an economist who I admire deeply and know personally and while he doesn’t need me to defend him, Steve’s accusation piqued my curiosity.

It was clear that Steve was referring to a specific interaction, and once George joined the thread the source of the issue appeared to have been a misunderstanding. Here is what happened:

Steve had made a claim about the standard, traditional, textbook version of the Money Multiplier (MM) model.

George had made it clear that while not endorsing the MM he objected to Steve’s depiction of it. He laid things out step-by-step.

Steve attempted to use his software, Ravel, to reveal a flaw in George’s claims, and therefore in the MM.

Here is a link and a screenshot of Steve’s “proof”:

Note the phrase “precisely what George asserted in his tweet stream”. Indeed, here we see a direct link between George’s tweet and Steve’s output in Ravel:

At this point, you do not need to know anything at all about money and banking to understand that Steve had seized upon George’s bad wording and that his conclusion was a result of his (incorrect) interpretation of what George had said, rather than the logic of George’s intended argument.

Erik managed to pin Steve down on this. Here is a summary of their exchange:

Erik: @ProfSteveKeen is there anything wrong with my, and therefore @GeorgeSelgin's, accounting now that all the misunderstandings has been cleared?

Steve: The error is that… Joe gets a liability (debt) with no asset (money) at this point. There is no way around this.

Erik: you’re criticizing a series of transactions that George never meant to suggest… disregard his clumsy sentence regarding lending reserves. I think the transactions in my screen shot above represents George’s step 1 and 2. Do you find anything wrong with THOSE?

Steve: Apart from some poor labelling, no.

Hallelujah! Agreement? Right?

I posted the exchange, praising Steve for accepting that George’s argument was correct. He seemed to want to caveat it by saying that George’s reasoning rested on Post Keynesian ideas, but whatever. My focus was on accuracy, not labelling. So I was puzzled that he subsequently reverted to his accusation that George was wrong.

I found Steve’s stubbornness really interesting. One would expect him to acknowledge George’s clarification and to retract his claim. Instead, he continued to assert that George was wrong without even acknowledging that he had misunderstood him. And he did so by returning to the source of the confusion, which is the precise wording around whether a bank “lend its reserves” or “lends an amount equal to its reserves”. Rather than seize an opportunity for common understanding, he was knowingly making an assertion that is prone to being misunderstood.

So I decided to pursue this. I will provided an edited account of our subsequent exchange, and reiterate that you do not need to understand the economic concepts to understand what is going on here…

Anthony: is your claim that loans have to be in cash contingent on whether there is a mandated reserve requirement?

Steve: No. Regardless of whether there is a mandated reserve requirement or not, to "lend from reserves" as textbooks teach and Fed Reserve Chairs state, the loans must be in cash. The loan can't credit borrower deposit accounts without violating the rules of accounting.

Anthony: Why can't a bank credit a deposit account and thus assets and liabilities offset?

Steve: because it violates the rules of accounting.

Anthony: You're saying that when a bank provides me with a loan it doesn't obtain an asset??

Steve: Of course a bank gets an asset when it provides a loan: the borrower's debt rises.

Anthony: I asked "Why can't a bank credit a deposit account and thus assets and liabilities offset?" You replied "It's because it violates the rules of accounting." And now "Of course a bank gets an asset when it provides a loan" I'm confused.

The problem here is that Steve is fixated on the “textbook” model and believes that I am deviating from it in providing my response. Similarly, he only granted George as being correct if George admits to being a Post Keynesian. Steve’s focus is not on whether George or I are correct, but the textbook model. But here’s the issue: he accuses both myself and George of being mainstream economists who subscribe to that model! Hence my desire to base the discussion around what I think, rather than what Steve and I accept as being the “textbook” account. Clearly, there is a risk that the unspecified and uncited “textbook” account becomes a strawman. And thus Steve’s critique rests on his misinterpretation of certain claims..

Here’s what happened next in the exchange:

Anthony: do you accept that your screenshot from Ravel doesn't actually capture the scenario I provided?

[Note that I’m making it clear that I am talking about my understanding of banking, and not the logic of the MM]

Steve: If the Fractional Reserve Banking model has any meaning, you have to “Lend from Reserves”. I’m saying the model works if and only if loans are in cash.

Anthony: Rather than simply repeat your assertions, can you respond to my question?

He didn’t reply.

So I took the opportunity to post a snarky tweet where I mocked him for suggesting I get a copy of his software.

Then, to his credit, after repeated attempts to point out what he had ignored, he did return to my specific question. Here was the scenario I was talking about:

A bank decides to extend a loan by crediting a deposit account.

Steve showed how that looked in Ravel, and acknowledged that it was different than his first version (link):

All I wanted him to do was to acknowledge that a bank can credit a deposit account without violating the rules of accounting. Not because I thought this was a “gotcha!” but because I thought it was something we agreed on, and could therefore serve as a starting point to interrogate the real issue (which was whether the Money Multiplier story requires all loans to be made in cash). Eventually, we got there (link):

Anthony: do you acknowledge that this is different to the one you showed [previously]?

Steve: Of course I do!

Anthony: so you agree that your original analysis in Ravel didn't balance because you misunderstood the scenario being presented to you (rather than because I had relied on faulty logic).

Steve: No. I modelled lending from Reserves, which plenty of Neoclassicals (maybe including you) have described as non-problematic. I showed that it violates the laws of accounting. But endogenous money as in the Bank of England paper you criticize works just fine.

[Note that Steve is accepting that his first screenshot was based on how he thinks other people view things, not what they actually believe.]

Anthony: But you accept that it was your decision about how to model it, rather than the claim that I was actually making, that meant it didn't compute?

Steve: I was criticising Selgin FFS

Anthony: In this post you seem to be directing your response to me. So: do you accept that the reason the Ravel output doesn't balance is because of an assumption that you made, rather than whether my example makes sense?

Steve: I admit that I am modelling lending from reserves when I show this impossible situation.

Anthony: Can we try to work an example based on what I say, rather than what you think someone else is saying?

Yes, I know I am being pedantic. But at this point Steve tried to turn the tables, and asked me “How on earth do you think Reserves are integral to lending?“ Before following this path, however, I wanted an acknowledgement that Steve’s Ravel output was wrong because of his choice of input, and not the logic of my argument. Here was the breakthrough:

Anthony: I am keen to discuss that point further, but I'm troubled by your inability to acknowledge a very simple point - that your table is out of balance because of your assumption and not because of my example. Can we agree on that please?

Steve: Oh FFS Anthony, it was because George asserted that since banks could buy bonds with reserves, they could also make loans from reserves. I said bollocks to that, and showed why because of George's example, not yours.

So if you want an admission, yes. I was criticising George's assumption, not yours.

To which I triumphantly responded, pleased that my point was made (and could also be extended to how Steve treated George).

With that groundwork laid, I wanted to have a more substantive conversation about the topic. Steve asked me: “So tell me how you think banks make loans”.

I considered this to be a deliberately obfuscatory question, since he didn’t specify whether he was talking about theory (and if so which theory) or practice. Was this Steve’s attempt to move beyond a disagreement about the implications of the MM, and find out what I think?

Part of the problem here is contained in the fact that I referred to the Money Multiplier model. We might instead view it as an explanation, or a depiction. Perhaps even a story. What is notable is that no-one seems to articulate what they are actually talking about. I haven’t yet found an article that quotes directly from a standard economics textbook and explains why it is wrong. So I am skeptical about whether the claim is that it truly is wrong rather than flawed, incomplete, or no longer relevant.

All economists have been exposed to the concept of the MM at some point. There is general agreement about what it is, and I think there is a consensus that (i) it does not accurately explain how the banking system works today; (ii) it wasn’t a completely accurate and literal description of banking practice historically. The point is whether it was useful, as a pedagogical device, to approach the topic of money and credit creation, how policy decisions work through the banking system, etc.

The only mention of the Money Multiplier in my own textbook is this:

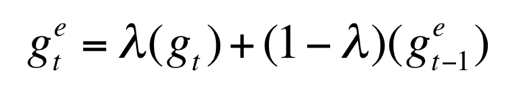

The money multiplier shows the change in the number of deposits for a given monetary base, and indicates the effectiveness of the bridge of intermediation.

Which isn’t great but certainly doesn’t form the basis of an explanation for credit creation. In a 2017 paper published in Economic Affairs, I argued that the concept of a “multiplier” is unhelpful and we should think in terms of ratios instead. But even though I’ve published research in this area, I am open minded about the validity of traditional economic concepts and I don’t feel that I have a solid grasp either of the theory or the debate. I approach this issue as a teacher, where my goal is for it to make sense. I am not approaching it as a heterodox economist aiming to distinguish myself from others.

My suspicions of Steve’s conduct, and intentions, can be seen in this exchange.

According to Steve, “George asserted banks could use reserves to make loans”. And yet George said “they can use [reserves] to finance loans”. [Emphasis added]. If the nub of the issue is whether reserves are being used as a direct source of fundings, this might not be a mere quibble. The subtle way in which Steve misrepresented George’s statement may in fact be telling.

I asked Steve to provide some context, because I want to avoid a situation where we spoke at cross purposes. And although I do not think that the monetary regime necessarily changes the logical coherence of the MM model, I felt it was important to agree on whether we were talking about the current system (where banks are not required to keep a certain proportion of deposits as reserves) or the previous system (where mandatory reserve requirements did play a role in monetary policy). So here is the conversation (link):

Anthony: I think the best explanation for how banks make loans depends on the monetary regime (e.g. whether there are mandatory reserve requirements, whether interest is paid on reserves, whether the supply of reserves is a policy objective or not). So I need more context to answer.

Steve: Do banks use reserves to make loans (a) with mandatory reserve requirements and (b) without interest paid on reserves and (c) when the supply of reserves is not a policy objective?

Anthony: I think that depends on what you mean by "use reserves to make loans". Do you agree that there's a difference between (1) immediately passing on newly obtained reserve balances to a customer; and (2) those reserves forming part of their constraint on lending.

Steve: Yes.

Anthony: Ok, and is the latter factually correct?

Steve: No

I found this answer interesting, because I drew a distinction around what I anticipated Steve would object to (that banks use reserves as a direct source of funding for deposits) and what I think is more defendable (that mandatory reserve requirements mean that reserves serve as a constraint on lending). So this was worth pursueing.

Anthony: So what are the main constraints on bank lending, when reserve requirements are mandated, if not reserves?

Steve: The willingness of banks to lever up (when creating loans) relative to their their equity, which is pro-cyclical.

Anthony: And does creating loans affect their reserve ratio?

At this point Steve simply posted a link to a CNBC article by John Carney called “Basics of Banking: Loans Create a Lot More Than Deposits”. I wasn’t sure if this was because he didn’t want to admit that yes indeed creating loans affects the reserve ratio, therefore reserves form part of a constraint on lending, therefore I was right. So I persevered:

Anthony: Are you saying, "yes it does"?

Steve: No it doesn't. But loans can trigger reserve requirements and equity raising after the event. You have the causal sequence backwards.

I didn’t, because my causal sequence started with loans.

Anthony So we agree that lending decisions have to give consideration to reserve balances?

But Steve wouldn’t be drawn! He said:

Steve: “You tell me whether you agree that loans create deposits first.”

I thought I had already dealt with that, so replied:

Anthony: I've already said, "A bank decides to extend a loan by crediting a deposit account". Does that deal with your question?

Which he interpreted to be confirmation that he was right all along and that the conversation was now over.

Steve: Yes. With reserves paying no role. So we’re agreed: banks create money by lending, and the money multiplier, fractional reserve banking, and loanable funds models are all false. Thanks. Now I’ll get in with my day.

But not so fast! We were actually very close to resolving the issue.

Anthony: Do you accept that lending decisions have to give consideration to reserve balances? (particularly in the context of mandatory reserve requirements)

Steve: Yes. They are a classic non-binding constraint, except for banks that are going under, like Northern Rock.

Anthony: Ok, so you accept that reserves *do* form a constraint on lending, but that ordinarily it is non-binding.

At this point the author of the CNBC article jumped in, and asked me:

John: Can you explain how you think they “form a constraint on lending” today? Or even under a reserve requirement system?

And Steve used that as an opportunity to bow out.

Steve: Tag team time... Over to you John!

Note how Steve’s position changed subtly (from “not a constraint” to “a non-binding constraint”) and instead of exploring what this (potentially critical) difference was, he attempted to shift the conversation away from answering my question (twice) and said that he would no longer respond (twice).

Here is my reply to Steve (which hasn’t been answered):

And here is my reply to John (also unanswered):

To be clear - neither of them owe me a response. But it seems telling that just as I feel I am on the verge of identifying an important, detailed point of difference… they go quiet. It is as if their aim is to make a point, rather than to seek common understanding.

I do not think I’ve identified a “gotcha!” here, and getting Steve to shift from “no constraint” to “what sort of constraint” doesn’t make me right and he wrong. But perhaps the fact that he didn’t make this concession implies that it is important. So although in the first conversation (about the Ravel output) I did manage to establish a starting point of agreement, on this occasion I didn’t.

I think I can make sense of things though.

Firstly, there is an issue relating to economic theory. It seems to me that there are really three issues to address:

Is the MM internally coherent?

Was the MM a useful way to understand the topic in the past?

Is the MM the best way to understand things today?

All sides seem to recognise that there are better ways to explain how banks operate today than through the concept of the MM so point 3 is by the by. (And therefore particularly irritating when people jump into a technical discussion about a specific context, such as whether the MM was a coherent concept in a world of mandatory reserve requirements, by arguing that “that isn’t how the present banking system works!”).

I believe that Steve wants to argue against 1, and feels that his reasoning carries over to point 2. And although George was willing to go all the way to defend point 1, I limited my arguments to 2. Indeed, I think this reveals why Steve is so repetitive about the phrase “banks lend from reserves” and so myopic about George’s correction that [banks] “lend an amount equal to its [excess] reserves”. ChatGPT seems to do a helpful job of summarising this issue:

Note that the extent to which that key phrase, “banks lend from reserves” is incorrect is based on a misinterpretation and an oversimplified analogy. But also telling that Steve attributes it to those he seeks confrontation.

The claim that “reserves constrain lending” is considered technically correct, albeit subject to context. This was what I was trying to drill down with Steve. But he did acknowledge that even in a mandatory reserve requirement regime the constraint is only “non-binding” ordinarily.

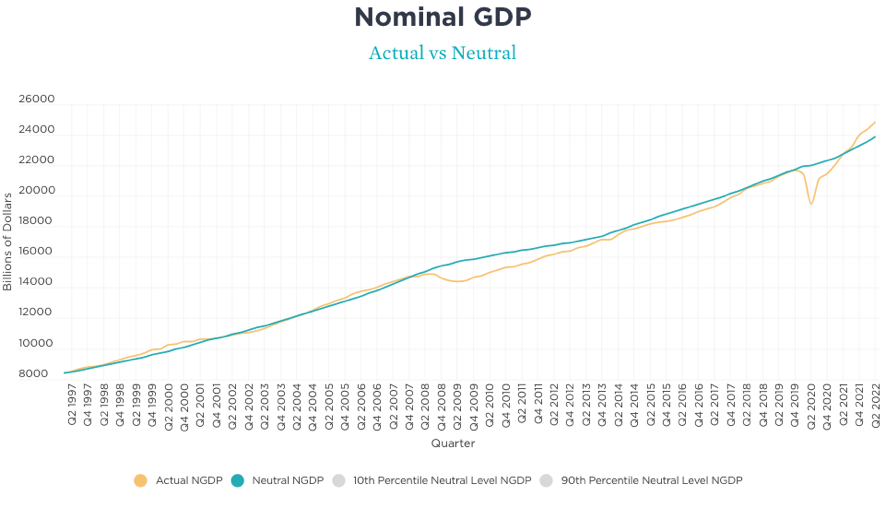

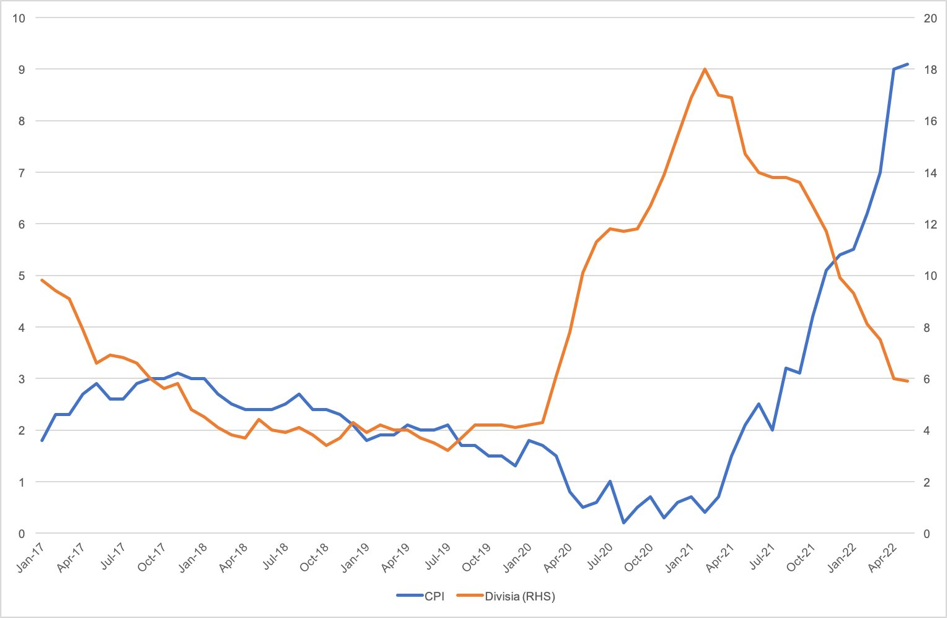

I think this brings us to the crux of the endogenous money argument. The “modern view” is a function of the monetary regime, and this isn’t fixed. When those who disparage the neoclassical, or mainstream, or MM, or fractional reserve position say things like “the supply curve for reserves is perfectly elastic, therefore they provide no constraint over bank lending” (or words to that effect) they gloss over the fact that this only holds at the designated interest rate. And that this is a policy choice.

This is a point made by George in his working paper, “Banks Are Intermediaries of Loanable Funds” (which I know Steve has claimed to have read, even if he didn’t link to it):

“It is of course true that any central bank interest-rate target implies a reserve supply schedule that’s horizontal at the targeted rate. It’s also true that, as long as it remains committed to a particular target rate, a central bank must allow the stock of reserves to adjust passively with the quantity demanded at that rate. But if monetary policy means anything in a rate-targeting regime, it means that the central bank routinely reconsiders its rate target, shifting the horizontal reserve supply schedule up or down whenever it sees fit to do so for the sake of meeting its macroeconomic objectives; and this ability leaves it no less in ultimate control of the outstanding quantity of reserves than it would be were it to instead target that quantity itself.” (p.33)

It seems to me a bit like saying that fixed exchange rates contain zero exchange rate risk. That’s only true as long as they hold. In a modern regime the profitability of funding opportunities constrain bank lending, but as George said here,

“loans are only profitable if they pay enough to cover banks’ funding costs, including costs of funding settlements—_not_ just the (near zero) cost of crediting borrowers’ accounts!”

I think that if we are arguing about how much of a constraint they are, and under what circumstances, then Steve has conceded the main point.

My second conclusion is that there is an issue here relating to the sociology of economic debate. As with X/Twitter discussions about MMT I have noticed a pattern:

Appeals to authority

A clearly cultivated internal language

A view that “everyone else” is wrong

A reluctance to enter into the detail of the issue

I consider myself to be a heterodox economist and so I recognise this phenomenon. It can be appropriate to enter a discussion and then pass over to experts once you get out of your depth. (Better than to keep digging a pit full of contradictions and absurdity that reflect your own intellectual gymnastics rather than the ideas you supposed to be grappling with). Amateur economists should be welcome. The elite institutions don’t have a monopoly on expertise. But it is cult-like and not conducive to intellectual debate.

It is beholden on those who make bold claims to provide a steelman of what they are arguing against. And their confusion should not be considered evidence of a faulty theory or model. If someone mocks a simplified explanation of a complex phenomenon on the grounds that it “doesn’t describe reality”, then they are in fact mocking themselves. I appreciate that these points are aimed more at Steve’s followers, rather than Steve himself. But he also has a responsibility as a public educator.

The Money Multiplier model is pretty redundant now, so failing to understand Steve Keen’s position won’t keep me up at night. But I hope this article serves as as a useful record of his imperfect conduct in a debate in which some are seeking clarity, and others practice sophism.