Last Thursday the Bank of England increased interest by half a percentage point, to 5%. As you can see, the recent trajectory and pace of interest rate changes have been significant:

The rationale is simple: the primary job of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is to keep inflation at around 2%, and it has remained stubbornly high. As you can see over the last 3 years, the conventional measure of inflation has been on a strong upward trend.

My explanation for what’s happened rests on a few claims:

The initial impact of Covid was primarily a negative demand shock, (not a supply shock), which therefore put downward pressure on prices. There was a necessity for monetary policy and fiscal policy to be accommodating and expansive.

Policymakers seemed to have learned their lesson from the global financial crisis by responding to the collapse in total spending by allowing subsequent spending to rise quickly. Rapid growth in the economy in 2021-2022 was necessary and important to return to the previous trend line.

The challenge was always going to be ensuring a “soft landing”. If they withdrew demand too quickly, we’d slip back into recessionary territory. If they failed to withdraw it early enough, we would have entrenched inflation.

Clearly Central Banks were naive about the extent to which high inflation in 2022 was driven by aggregate demand as opposed to supply side issues relating to post covid bottlenecks, and shocks to energy prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They’ve been complacent and have reacted to the threat of inflation too late.

Now, there’s a real danger of an overreaction. We can already see that inflation is subsiding. Once more interest rate rises flow through into the real economy, there’s a danger that by avoiding +10% inflation we fall below the 2% target, and cause a major and unnecessary slowdown.

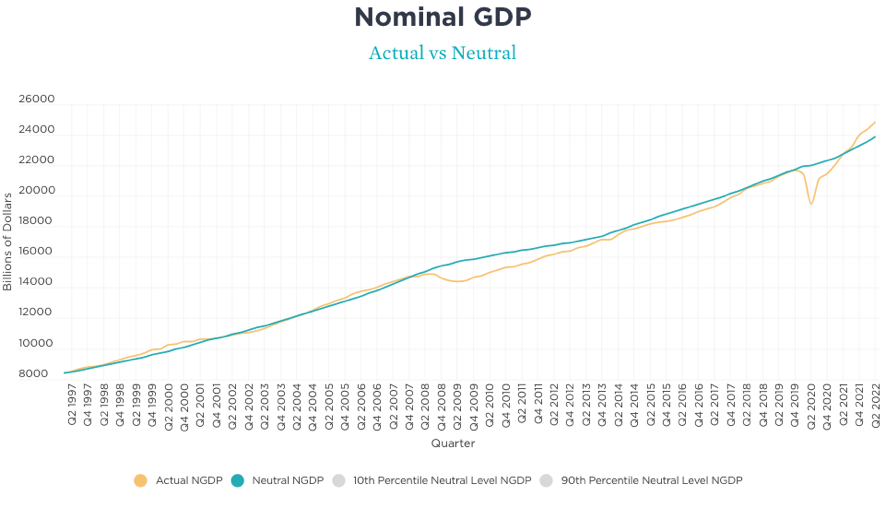

Back in December 2021 I discussed whether central banks were listening to those who argue that trend rates are more important than growth rates. I was hopeful, but consider this chart, published by David Beckworth in September 2022.

You can see three really important things:

In 2008/09 policymakers allowed NGDP growth to fall below where it needed to be to ensure neutral monetary policy, and for several years it stayed there.

In 2020 policymakers ensured that after NGDP growth fell below the neutral path it was then allowed to quickly catch back up again (big success!!)

As of 2022, however, it was overshooting and way above the rate required for monetary neutrality.

The above rests on my preference for using stable growth in the cash value of economic transactions (NGDP) as the optimal monetary regime. But you don’t need to advocate NGDP targets to be concerned by current central bank decision making.

When I teach monetary policy to MBA students I use an exercise called “Monetary Implications” which shows how to assess decisions from 3 perspectives. We can do the exercise now:

Money growth rule

Broad money growth has been slowing for some time and is now just 1.6%. Divisia money growth is an even bigger concern, contracting by -2.9% in April.

Inflation target

As already shown, inflation is high. CPI is growing at 7.9% and core inflation seems worryingly stubborn.

NGDP target

2023 Q1 saw growth of 6.6% which is higher than the average prior to covid (which was around 4%), but it has fallen in every quarter since the start of 2021. The MPC don’t explicitly target NGDP so there’s no reason to think they are paying close attention to it. But my major concern is that the current path of interest rate rises will reduce total spending such that NGDP continues to fall below the long term appropriate rate of around 4%.

Here’s a summary:

If all three alternatives point in the same direction, policy decisions are non-controversial. The problem now is that money growth data and inflation data provide two polar opposite implications for policy. If we use NGDP as a decider, I think that the greater concern for downward trend probably means that we should be more cautious about waiting for the consequences of previous interest rate decisions to pass through. These are strong reasons against raising interest rates. Even more importantly, the real focus should be on market expectations regarding where these indicators are heading. If it’s the case that inflation expectations have become dislodged from the 2% target, while NGDP expectations are also on a decline, we have a truly terrible situation where we’ve chosen the wrong policy objective and failed to even achieve that. Scary times ahead.

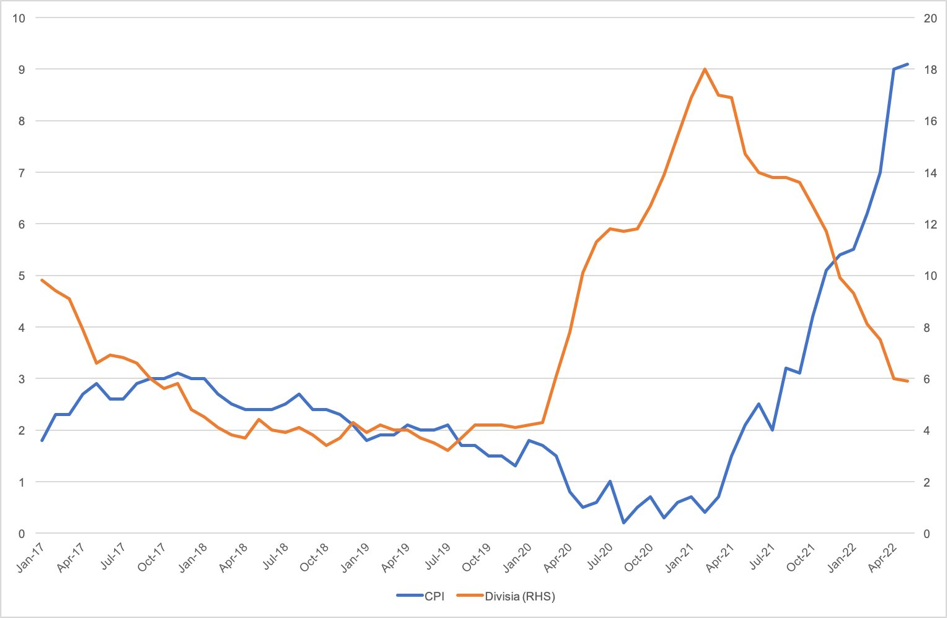

Finally, I’m not a monetarist, but I think it’s important to acknowledge those who’ve been warning about high inflation for some time, and also when they stopped worrying about it. I’ve been using this chart for the US since January 2023:

It shows high a big increase in M2 preceded the rise in inflation. It also shows that M2 subsequently became negative, and that inflation was starting to fall.

Here’s data from the UK from mid 2022. Once again, and as standard old fashioned monetarism implies, the inflation measure follows what happens to the money supply (in this case I use a Divisia measure). If we expect that relationship to continue, our concern is about falling inflation not persistently high inflation.

Raising interest rates under the current circumstances seems to be a case of too much, and too late. Things would have been better had the MPC taken inflation more seriously in 2021, but that’s in the past. They shouldn’t make a new error in response.